A foster child beats the odds to join the bar

By Diane Curtis

Staff Writer

Life for Tyrone Wilson could easily have taken a very different path. One of 10 siblings, he lived in 20 foster homes in San Jose and the San Joaquin Valley after his drug-addicted mother lost custody of her children when he was six. He never knew his father. He was often in trouble – especially in elementary and middle school – for stealing and fighting other children, sometimes with scissors. Sometimes he was a good student and sometimes he was not.

But last month, surrounded by friends, some former foster parents and his mother at a Tulare County courthouse, the 28-year-old high school football hero and graduate of the State University of New York at Buffalo (undergraduate and law school) was sworn in as a member of The State Bar of California.

"It's a very unusual story," said Superior Court Judge Valeriano Saucedo, who has been a mentor to Wilson and administered the oath. Saucedo laments that it is far more likely for him to see kids who grow up in the "300 system" – the dependency court system – end up in the "600 system" – the juvenile criminal justice system – than to see them reach adulthood as productive citizens.

|

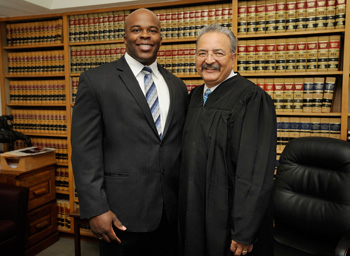

Tyrone Wilson and Tulare County Judge Valeriano Saucedo

in the judge's chambers. PHOTO: Steve R. Fujimoto

|

"I think that one of the issues in the juvenile system is that many times kids do not understand they can have big dreams and make those dreams come true," said Saucedo, who was taken up on his offer to help Wilson study for the bar exam after Wilson failed three times. (He passed immediately after studying with Saucedo.) "Once he connected with some excellent foster care parents, he realized he could have as big a dream as he wanted and that there were people in his corner who could help him achieve that dream," Saucedo said.

Wilson's time in foster homes ran the gamut, from good to awful, from brief (two weeks) to longer. There was a home where he ate outside while the rest of the family ate together inside, a home where he was not allowed to take even ice water out of the refrigerator without asking, a home where the Christmas presents for the biological kids were significantly different from the gifts for the foster kids. Sometimes, the biological children of the foster parents resented the intrusion of a foster child, and that meant getting booted out and finding a new placement. At some homes, Wilson witnessed physical abuse. Not just once he was told by foster parents or teachers that he would amount to nothing, that he would end up dead or in prison. He was often told how grateful he should be just to have a place to live. And in some respects, he agreed. "They would give me three hots and a cot," Wilson says resignedly. "I can't complain."

He was then, he says, "very, very angry and frustrated. I didn't trust people. I was fighting, stealing, cursing." At the same time, he knew he wasn't a bad kid and that he wanted to get out of the hole he was digging for himself. "But I didn't know how."

|

Judge Saucedo swore in Tyrone Wilson June 3.

|

He got a nudge in the right direction from some caring foster parents: Jess and Donzella Washington in Pixley; Cathy Frusquillo, Carlton Jones and Tia Coleman, Bobby and Carmen Jacobo, Ronnie and Steve Wilbur in Tulare.

In eighth grade, he was expelled but wanted another chance. The principal was having none of it. Then Frusquillo went to the principal's office, was heard talking in a rather forceful manner, came out and told Wilson he was back in school. "Don't prove me wrong," she said to him. "I never forgot that," he recalls. "I think from that day forward, I realized I didn't want to prove her wrong." With others, like the Washingtons, regular chores and discipline were welcome because he felt like a family member. And Jess Washington, a hard-working respiratory therapist, became one of the few black male role models in his life.

School success was sporadic and inconsistent. When he was eight, and back at his mother's house for a short time, his stepfather asked him to go find his mother. "My mom was running the streets. When you're in that type of environment, you can't really focus on school." Yet later he would "burn through" a year's worth of math instruction in a few weeks because he felt like it. And he devoured books like A Wrinkle in Time in fourth grade ("I chose it because I liked the cover") and Catch-22 in sixth grade ("That one had me confused") when he'd spend hours at the library because one family did not want him in their house.

Despite the occasional backslide, Wilson did get his act together in high school. Frusquillo let him know that college wasn't just an option; it was a given. "I was at a point in my life where I wanted to change," Wilson says. "I always wanted to be a good kid. I was always a bright kid." He played football, did his homework, became a drum major in the band, got a football scholarship to Fresno City College and then another scholarship to Buffalo. And then, after his tutoring with Saucedo, he became a lawyer. Currently, he's working on a contract basis for a criminal defense lawyer while looking for full-time work, preferably in transactional law, with an eye toward a possible political career.

Wilson says he's "blessed" to have had some very good people in his life, like some foster parents, mentors at Griswold, LaSalle, Cobb, Dowd & Gin LLP, where he was a clerk, and Saucedo, who was critical to improving his writing skills and understanding legal fundamentals.

But his life experiences – good and bad – have informed him, he says. "I know people. If I talk to anyone longer than five minutes, I know their motivation." Wilson said his experiences have trained him how to adapt "and that's what's going to help make me a good attorney." Transactional law is his preference because, he says, unlike litigation, where there's a winner and a loser, transactional law can produce two winners. "I had a professor who said, ‘If both sides feel they won, that's a great transaction.'"

Judge Saucedo sees Wilson succeeding in whatever he does. "I thought he was incredibly bright and determined, and I think that to be successful with his background, you have to have those two elements. Fundamentally, he's very smart – just a real intelligence about him. He's such a unique individual with a real good set of skills. I just don't see him not being a success. I expect great things from Tyrone."