Recession-related suits a drain on courts

By Diane Curtis

Staff Writer

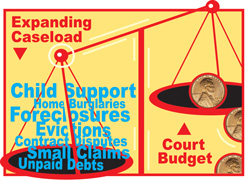

It’s a vicious circle: Defendants seek community service because they can’t pay the fines of a traffic citation or a conviction. The courts lose revenue and have to compensate with overworked staff or reduced programs or delays — or further increases in fees and fines — as a result of decreased funding. At the same time, the number of cases coming to the courts — although not necessarily going to trial — is escalating because the recession has resulted in more foreclosures, more evictions, more contract disputes, more home burglaries, more petitions for expungement, more petty theft, more small claims, more requests for a change in alimony or child support, more domestic violence, more unpaid debts. And all this is happening when the state can’t pay its bills, resulting in furloughs and cutbacks, although a May revision of the budget indicates those furloughs in the courts may end.

It’s a vicious circle: Defendants seek community service because they can’t pay the fines of a traffic citation or a conviction. The courts lose revenue and have to compensate with overworked staff or reduced programs or delays — or further increases in fees and fines — as a result of decreased funding. At the same time, the number of cases coming to the courts — although not necessarily going to trial — is escalating because the recession has resulted in more foreclosures, more evictions, more contract disputes, more home burglaries, more petitions for expungement, more petty theft, more small claims, more requests for a change in alimony or child support, more domestic violence, more unpaid debts. And all this is happening when the state can’t pay its bills, resulting in furloughs and cutbacks, although a May revision of the budget indicates those furloughs in the courts may end.

“When the economy forces people to avoid their obligations, lawsuits increase,” says Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Robert Dukes in the court’s annual report. “We in the trial courts are forced to address these mounting concerns with dwindling resources.” Adds his colleague, Judge Gail Ruderman Feuer: “The recession is straining our misdemeanor courts to the limits and confounding our capacity to deter and rehabilitate offenders.

And it goes on: People who can’t pay their fines also can’t pay mandatory fees. That can mean more jail time and more crowded jails as well as lost income (if there was money coming in), and in turn more foreclosures, more evictions, etc. The courts feel the brunt in longer court cases and delays when people can’t afford attorneys. People who represent themselves need more help from the clerks and the judges and often draw out a case that could have been settled out of court or dispatched more quickly and easily if lawyers were representing them. Also, especially in family law cases, confrontations get more heated because the middle man has been eliminated.

In San Francisco, 2009 employment claims were up 89 percent over 2007, eviction and other unlawful detainer cases up 49 percent, collections up 32 percent and breach of contract cases up 25 percent. The latest figures for Los Angeles show a 33 percent increase in evictions and other landlord-tenant disputes and a 22 percent increase in small claims. “Generally, litigation rises in an economic downturn as regulators tend to step up enforcement, laid-off workers head to court and companies need to file more suits in order to collect on money owed,” says Stephen Dillard, head of Fulbright and Jaworski’s global litigation practice.

“Not many a day passes without my receiving an emergency ex parte motion seeking to stop a foreclosure or eviction, and they’re increasing every week,” notes Los Angeles’ Dukes. “Once a trickle, they’re now rapidly flowing, and we’re prepared for a flood.” His colleague, Judge Mary Thornton House, says almost all civil litigants claim indigence and ask for a waiver of court fees. “Although the applicants are genuinely needy, granting a fee waiver takes water out of a well that cannot be replenished.”

Dukes says defendants going through bankruptcy in federal court require him to stay proceedings on his own calendar. The once-infrequent requests by loan holders for writs of attachment or writs seeking protection from garnishment “are now an everyday occurrence.” Nationwide, bankruptcy filings are at their highest since 2006, with a 27 percent increase between March 2009 and March 2010. Most of the additional bankruptcies involve personal and consumer debt. While the filings throughout the country averaged 4.92 per 1,000 people, they averaged 6.15 per 1,000 in California, the eighth highest in the country.

While those who have to declare bankruptcy lose their homes and lifestyles, others who maintain their good credit and live within their means can also be innocent victims of the economy. Presiding Judge Tom Cahraman of the Riverside County Superior Court says it’s especially painful to see so many people who have faithfully paid their rent get evicted because the landlord lost the home. “It’s bad to get evicted. It’s really bad when you’ve paid your rent,” he says, noting that Riverside eviction and small claims cases are “up sharply— – as they are in other counties. Those cases, along with traffic offenses, create long lines at the courthouses. As one effort to alleviate long waits, he’s created a pay-only window that doesn’t require visitors to go through court security and wait with others who need more complicated help. They can hand in their check and are done. The effort to quickly and efficiently add traffic fines to court coffers is strategic: With revenue cuts, courts have turned to traffic and other fees as an alternate source of revenue.

As one in a number of Catch-22s in the current economic crisis, Cahraman notes, Riverside is far short of the judges it needs to handle the number of court cases in one of the fastest-growing counties in the state (San Bernardino also is setting growth records). Yet allocations for state money are based on thee number of judges. “We are doubly disadvantaged because we are greatly underresourced in terms of judges … Everybody in Riverside is working like crazy.”

While the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia reports that divorces have declined during the recession (some experts say the reason is people can’t afford divorces), court officials advise that issues involving divorce have not. Bonnie Hough, equal access attorney for the Administrative Office of the Courts, says court self-help centers are reporting more modifications of child support and more domestic violence cases, yet the litigants can’t afford an attorney because they have lost a job or the equity in their home or their pension. One Los Angeles courthouse experienced a threefold increase in applications to reduce child support payments, and the courthouse is jammed. One response by the court has been to help litigants prepare their documents in groups of three to six. Also, more business is done by phone and mail rather than requiring people’s physical presence.

And then there are juries. More people are asking to be excused because of financial hardship.

If the economy continues as it has and the state does not make up the shortfall, Micronomics, a Los Angeles-based economic consulting firm, states that lost court days and reductions in operating capacity will result in a decline of $13 billion in business activity statewide resulting from decreased use of legal services, a reduction of 150,000 jobs and $30 billion in lost output because of the uncertainty among affected businesses of delayed disposition of cases. But there is daylight in the economic future. Governor Schwarzenegger’s office and the state legislative analyst have said the worst of the recession is over and predicted an improved economy in the next two years. Still, any recovery will be slow and not enough to make a significant dent in the unemployment rate.

Chief Justice Ronald George, however, says that if the governor’s May revision restoring $100 million for the courts that was targeted for elimination holds and a legislative package that adds revenue goes forward, “although times will still be very difficult, the courts should be able to get through the coming fiscal year without any statewide court closures and, hopefully, without locally ordered court closures or further layoffs and without jeopardizing our two basic infrastructure objectives” (moving ahead with courthouse construction projects and implementing a new case management system).

The current cutbacks to the court system, George notes, and something he told the governor last month, “are not a luxury to be funded in good times and ignored in bad times. They provide one of the most fundamental and important services provided by the government.” The closed courts are especially troubling, he says. “It’s not the same as seeing a closed sign on a DMV office. The symbolism of going to a courthouse where one expects to find justice and seeing a closed sign is very, very negative in terms of people’s faith in government.”

Still, George says the bad economy’s effect on the courts would be “far, far worse” if California’s justice system were still funded by the counties and not the state. “The state funding mechanism has given us a much better means of coping with the cycles,” he says. “Difficult as present times are, it would be far, far worse if we were under the old system of courts competing with law enforcement, libraries and public health.”

Foreclosures swamping State Bar discipline

The slew of foreclosures caused by easy loans and the recession has hit the State Bar’s discipline system hard. Investigations increased more than 90 percent between 2008 and 2009, and Interim Chief Trial Counsel Russell Weiner says complaints against attorneys offering loan modification and other debt relief services accounted for the big hike.

Emergency proceedings to promptly remove attorneys posing the greatest risk of harm to the public also increased, as did dismissals, terminations and resignations with charges pending. And despite a slight improvement in the economy, the State Bar has seen no decrease in the number of new complaints in recent months, Weiner says.

At the same time, reports from banks of overdrawn client trust accounts continue to grow, jumping 53 percent between 2008 and 2009 alone. Before that, such reports had shown steady declines.

Applications for payments from the Client Security Fund, which compensates clients who lose money due to a lawyer's dishonest conduct, also have skyrocketed, with more than 3,000 applications filed in 2009 compared to 800 in 2008. “From what we’ve been seeing, it isn’t more large claims but lots and lots of small claims,” Bill Hebert, chair of the Board of Governors’ Discipline Oversight Committee, said at a board meeting last month. Many of those claims are from clients who sought loan modification help and paid $2,000-$4,000 to the attorneys without seeing a change in their loan payments.

Coupled with the need to address the recession-related bump in complaints and investigations, the bar added to its responsibilities in 2007 greater regulatory action over non-attorneys engaging in the unlawful practice of law.

“All of this has resulted in a greatly increased workload for the office at a time when the office has not been in a position to add any new staff due to budgetary concerns,” says Weiner. “Taking everything into consideration, I believe the office has done a great job, but still has a long way to go.”