A hundred years later, a trailblazer gets her due

By Kristina Horton Flaherty

Staff Writer

Just before midnight on April 1, 1878, Clara Shortridge Foltz, a young mother of five, bolted through a horde of men into the California governor’s chambers. She could not accept the news that the unsigned Woman Lawyer’s Bill — legislation entitling women to practice law — was dead. But, as Foltz’s account goes, the governor listened to her appeal, then retrieved the bill from a discard pile and, just moments before the midnight deadline, signed it into law.

The historic moment was just one of many in Foltz’s once-celebrated career as the first woman lawyer on the Pacific Coast, California’s first female deputy district attorney and the founder of the public defender movement. She sued for entrance into California’s only law school, tried cases in court when women were not allowed to serve on juries and played a key role in winning women’s suffrage in California 100 years ago.

But Foltz’s renown then virtually disappeared, and for decades her remarkable story lay buried in old court transcripts, letters and countless newspaper clippings preserved on microfiche.

|

| Barbara Babcock |

“She was so famous in her day and did so much and yet she was just completely forgotten,” says retired Stanford law professor Barbara Babcock, who recently finished the first and only biography of Foltz after years of research.

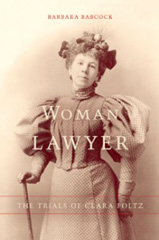

Babcock’s new book, Woman Lawyer: The Trials of Clara Foltz (Stanford University Press 2011), tells the unlikely story of a young girl who elopes with a Union soldier at age 15, begins married life on a farm in the Midwest and bears five children — then goes on to become a lawyer, suffragist, newspaper editor, influential thinker and popular orator who once captivated audiences nationwide.

Much of the story unfolds in the late 19th century, a time marked by turbulent politics, a rapidly changing way of life and a sense of hope. In telling Foltz’s story, Babcock reveals the links between the suffrage movement and other struggles for civil rights and legal reform. And she shows what Foltz and her fellow suffragists faced in their push for the vote and equal access to education and employment, and the right to serve on juries in California. Opponents argued, for example, that women voters would simply vote for the best-looking candidate and that women lawyers would seduce male juries into acquitting the guilty. They even warned that such activities would change women by “unsexing” them.

Foltz’s story first caught Babcock’s attention back in the 1980s. The Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office was looking for a historian to write something about Foltz as the founder of the public defender movement. Babcock was “astounded,” she recalls, to learn that a 19th-century woman had pioneered the idea of a public defender.

She also felt an immediate connection. Babcock herself, at age 30, served as the first director of the Public Defender Service in Washington D.C. from 1968 to 1972, and was the first woman appointed to Stanford Law School’s regular faculty. And from her days at Yale Law School in the early 1960s, when less than 4 percent of the nation’s law students were women, Babcock knew what it was like to be one of just a few women seeking a legal career. A close male friend of hers at the time once insisted that women were not cut out to be lawyers and noted, as proof, the complete lack of great advocates, famous judges and brilliant scholars among women in the law.

But in Foltz Babcock found such a lawyer — and a piece of buried history.

Reconstructing Foltz’s life story turned out to be a painstaking project. Many warned it would be impossible to compile a complete biography or was simply not worth the effort. Foltz’s personal papers were nowhere to be found; her sole heir had auctioned them off with her other belongings within days of her death in 1934. And while Foltz was known for keeping scrapbooks, their whereabouts were unknown when Babcock began her research.

Reconstructing Foltz’s life story turned out to be a painstaking project. Many warned it would be impossible to compile a complete biography or was simply not worth the effort. Foltz’s personal papers were nowhere to be found; her sole heir had auctioned them off with her other belongings within days of her death in 1934. And while Foltz was known for keeping scrapbooks, their whereabouts were unknown when Babcock began her research.

But, recalls Babcock, “I never really got discouraged because I always knew there would be enough to make a story.” She pored over old newspapers from Foltz’s era (a time when there were 21 daily newspapers in San Francisco alone) and, with the help of law students and assistants, tracked down interviews and yellowing court transcripts from appeals in Foltz’s cases.

Eventually, she even found one of Foltz’s long-missing scrapbooks in the bowels of the Huntington Library in Pasadena but quickly discovered, in a “heart-pounding” moment, that it contained very little personal information.

“It was mostly clippings from a clipping service,” Babcock said, “but her hand pasted them in.”

What emerged through Babcock’s research was the eventful life story of an ambitious, idealistic, energetic woman who, with very little formal education, saw no limits to what she could accomplish.

In the mid-1870s, Foltz studied law at her father’s law office in San Jose. And on Sept. 5, 1878, just months after the enactment of the Woman Lawyer’s Bill, she became the first woman admitted to the California bar.

Less than a year later, she and fellow suffragist Laura Gordon helped win inclusion of two unprecedented clauses in the California Constitution guaranteeing equal access to employment and education for women. And she filed, and eventually won, a lawsuit seeking entrance into Hastings College of Law in San Francisco.

Foltz’s marriage ended early in her career. But as a divorced mother of five, she continued to practice law and to champion legal reforms and women’s rights. On the lecture circuit, she was dubbed the “Portia of the Pacific.”

Once, in 1884, Foltz and a fellow women’s rights advocate half-jokingly sent a telegram to Washington D.C. attorney Belva Lockwood with the news that the Equal Rights Party in San Francisco — a nonexistent party with a made-up name — had nominated her for the U.S. presidency. They did not really expect an answer, Foltz would later recall. But to their surprise, Lockwood accepted the nomination and, soon after, reporters showed up at Foltz’s door asking questions about the nonexistent party.

In California, Foltz became the first woman to serve as a legislative counsel, to prosecute a murder case, to hold statewide office (the State Normal School Board), to become a notary public and to serve as a deputy district attorney.

Still, she uprooted her family many times in a seemingly endless search for greater acceptance, fame and fortune. She practiced law in San Jose, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Denver and New York, and, at one point, founded and edited a daily newspaper in San Diego. She also continued to push for women’s suffrage, eventually becoming one of the few original suffragists who lived long enough to cast a vote.

“She really was very present to history, and very involved in everything that went on,” Babcock said. “Sometimes I think of her as the Forest Gump of the 19th century.”

From Babcock’s perspective, Foltz’s greatest achievement was her role in the nation’s public defender movement. Foltz’s early experiences representing indigent clients and witnessing shysters, incompetent defense lawyers and prosecutorial misconduct led her to come up with the idea of a public defender to balance the public prosecutor.

In 1893, she presented her concept at the Congress of Jurisprudence and Law Reform at the Chicago World’s Fair as a California bar representative. She later drafted a model statute and campaigned for its introduction in numerous state legislatures. The first public defender office opened in Los Angeles in 1913 and the “Foltz Defender Bill” was adopted in 1921 in California. “She was way ahead of the times in her thought,” Babcock said.

For years, Babcock juggled her full-time teaching job at Stanford Law School with her research into Foltz. “I felt that I knew her on this deep level, and there’s this aspect of rescue,” Babcock recalls. “What it led me to see was that her only chance to be famous was me.”

And over the years, Babcock’s many articles and lectures on Foltz did spark new interest. In 2002, largely based on Babcock’s biographical work, the central criminal court building in Los Angeles was renamed the Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center. Still, even then, an article in the Los Angeles Times asked: “Clara Who?”

Recently, Babcock characterized Foltz’s life as “both a heroic example of living to the full and cautionary tale about the limits of the possible.”

Foltz never struck it rich and, in later life, expressed some regrets about missing time with her children. She reportedly felt underappreciated and even wondered at times if her efforts had been worth it. But after years of research, Babcock has come to see Foltz as the most important pioneering woman in California of her time — a brilliant, brave trailblazer who deserves greater recognition for what she accomplished.

Sometimes, Babcock says, she even asks herself: “What would Clara do?” In one instance, for example, Babcock turned down a request to testify before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in Robert H. Bork’s confirmation hearings for the U.S. Supreme Court. She was busy working on Foltz’s biography and figured that her husband, who had agreed to testify, could represent her views. But after hanging up the phone, she suddenly thought of Foltz, who would have traveled for five days by train to Washington D.C. for such an opportunity. “And so,” Babcock said, “I went.”

These days, Babcock is spending much of her time introducing Foltz to a variety of audiences, from the Half Moon Bay Rotary Club, where she sold 30 books, to a public defenders’ convention to the London School of Economics. Throughout it all, she says, she feels as though she has rescued California’s first woman attorney from obscurity. “I feel like I’m just giving her her chance.”

• For more information on Foltz and how to order “Woman Lawyer: The Trials of Clara Foltz,” visit Stanford Law School’s Women’s Legal History website.